Reading experience disclaimer: our blog posts contain annotations that are often more interesting than the content itself. On your phone, annotations will show up in between paragraphs. On larger screens, you’ll see them on your right, next to the paragraph they’re meant to expand upon. All footnote numbers are clickable and lead to the corresponding annotations.

You may have seen it already—we’re in a New York state of mind these days.

While working on the Pieces of New York collection, as we were randomly browsing the discount section of Mast Books on Avenue A, we stumbled upon a used copy of the 1989 book New York Fashion: The Evolution Of American Style by Caroline Rennolds Milbank. The tome is incomplete, with a lot of the images having been cut out, likely to feed someone’s moodboard—yet it still offers one of the most comprehensive deep-dives into the history of fashion in America in general and New York specifically, with plenty of information and visual references to New York designers whose work helped shape American fashion as we know it today; even if their names are less recognizable than your Donna Karans and your Calvin Kleins.

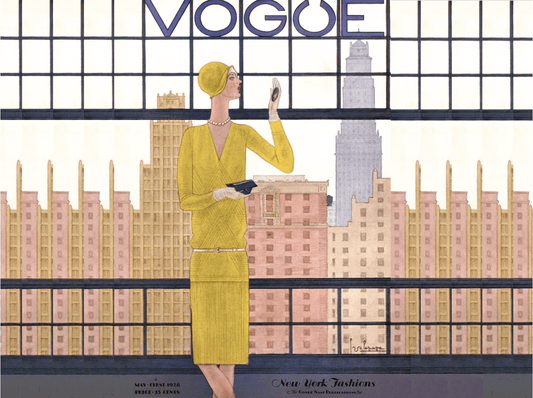

New York Fashion seems to be out of print but you can still find some used copies online, both on Amazon and on places like ThriftBooks. Here, as our own mood-setting exercise, we transcribed the entire introduction of the book, serving as a good TL/DR of sorts to help contextualize what we talk about when we talk about New York fashion. The annotation images and captions are also from the same book, just a small sample of the imagery accompanying Milbank’s research. The featured visual for this post was created using this Vogue magazine cover—while the images you’ll see within the post are taken from ThriftBooks, AmericanFashionMagazines.com, and (!) CivilWarTalk. References does not own any of these images; we’re only referencing them for the purposes of research and fashun nerding-out.

Whether or not there is such a thing as American fashion is still being debated, and misconceptions about what is designed in this country abound. It is not true that America invented ready-to-wear, or sportswear, or even the concept of department stores. It is not true that Americans merely copied the French, or that American clothes were less well made than those from Europe. It is especially untrue that American fashion would never come into its own if Paris hadn’t been occupied by the Germans during World War II.

What is true is that American fashion existed long before the 1940s and was centered in New York by the middle of the nineteenth century. The first American fashion was made to order, and when ready-to-wear came into being, it supplemented rather than replaced custom-made clothes. Fashion in this country was a blend of hand and machine work, with the distinction between retailers, manufacturers, and designers blurred. Out of this group, designers rose to prominence during World War II. Before there was an American fashion, there was an American style. It has its genesis in the patriotic determination, after the Revolutionary War, to wear homegrown, homespun, and home-sewn clothes, following the example of George and Martha Washington as well as such religious groups that had sought freedom in this country as the Amish and the Quakers. Relying on imported goods reflected poorly on America’s independence, and ostentation in dress was viewed as epitomizing the rigidly delineated way of life under a monarchy. Simplicity in dress celebrated both self-sufficiency and the freedoms inherent in a democracy. However, as the country prospered, a taste for opulence grew, and beginning around the middle of the nineteenth century ostentation served as an outward and visible sign of an inward and invisible ability to get ahead. Those amassing vast fortunes built European-style houses, collected French, Italian, and English art and furniture, and dressed in Paris clothes. In doing so, they displayed a pervasive native inferiority complex about America’s capacity to produce its own art and, along with art, luxury goods. It is interesting to note that when Americans were criticized for lacking taste, it was almost always when they were aping Europeans.

The nineteenth-century preoccupation with French fashion had grown out of a desire to avoid importing goods from England, so recently America’s nemesis. France had long enjoyed a reputation for marvelous fabrics and trimmings, as well as for the wonderful clothes made out of them and worn by French beauties, particularly at court. However, it was not until Charles Frederick Worth in the 1860s established himself as an artist of fashion that the couture became a unified entity in which a dress, as created by an artist, was greater than the sum of its parts. Worth acted as the catalyst to transform French fashion (composed of products from around the country) into Paris fashion. New York was already at the center of American Fashion. New York supplanted previously fashionable centers like Boston and Philadelphia when, with the invention of the steam-powered ship in the 1820s, the Hudson River became easily navigable, making New York’s port doubly convenient. Within two decades, the number of merchants purveying all kinds of fashion-related wares greatly increased, although their primary trade was in imported materials and trimmings rather than actual clothing. Along with these dry-goods stores, which would develop into mammoth bazaars selling everything from $2,500 shawls to fabrics available for a penny a yard, catering to every level of society, there were by the 1850s grand dressmaking-import houses that made luxurious clothes to order.

While Paris dresses were displayed prominently in the windows of emporiums like A. T. Stewart, Lord & Taylor, or Mme Demorest—just as magazines and newspapers published fashion plates showing couturier clothes—what was actually available to buy was a store-made version of the dress in the window or plate. Paris dresses were rarely copied faithfully; instead, they served as departure points to American seamstresses, custom dressmakers, and the first ready-to-wear manufacturers. New York stores, which sold on both a retail basis to their own clients and wholesale to merchants around the country, served, along with the fashion magazines that were based in New York, to inform the rest of America about what was in fashion.

New York didn’t copy Paris, it used it. The very words French and imported meant money in the till, and it is the rare nineteenth-century label that does not read Mme ________, Importer, or _______ & Co., New York and Paris. As the Paris couturiers became known by name, New York designers/custom dressmaker effaced themselves all the more. They downplayed their own participation in their designs, content to imply that Paris had been responsible. By the twentieth century false Paris labels were being sewn into New York couture designs. Ready-to-wear clothes, clearly not comparable to the products of the Paris couture, bore on their labels only the names of the stores in which they were sold, not those of manufacturers or designers.

Part of why Paris cachet was so important was that the fashions themselves were not always pertinent to American women, who, by the Civil War, had begun to be interested in getting an education, in trying their hands at jobs previously held almost exclusively by men, and in engaging in athletic endeavors. Their growing independence was hampered not only by the more ornate and restrictive nineteenth-century fashions themselves but also by the convention of following fashion, easily a full-time occupation. As American women began to establish a preference for simpler clothes, like shorter skirts for walking and jackets and/or shirtwaists and skirts for all-day wear, the ready-to-wear industry was finding that just such simple clothes best suited the limitations of its rudimentary machinery. Simplicity is an element of American fashion, in terms of both manufacture and style, that cannot be overemphasized. By the end of the nineteenth century, supply and demand had resulted in a style that would be epitomized by the Gibson girl’s shirtwaist and skirt, a fashion that was easily manufactured and appropriate to all classes. Even as American style and fashion were rising to the fore, many Americans had found Paris a difficult habit to break. Before World War I there were rumblings about whether American designers should be given more credit. More than a decade later Lois Long, the fashion writer for the just-established magazine the New Yorker, broke precedent by covering those designers previously known by name only within the industry. And it was a bold move when Dorothy Shaver at Lord & Taylor in 1932 began promoting American designers in various ways, including having such couturiers as Elizabeth Hawes and Muriel King branch out into ready-to-wear. Throughout the 1930s awareness of American fashion grew, and in 1938 Vogue initiated its annual Americana issue.

This slow but sure progress toward recognition of American fashion accelerated during World War II. Since Paris was actually occupied, its couture was much more curtailed than it had been during World War I. New York fashion magazines promoted local talent, not simply because it was patriotic and the fashion themselves good, but because they had no choice. And so at last designers who had long been known within the industry, like Claire McCardell, became familiar to American women. Although the couture regained its position after the war, especially once Christian Dior opened his own house and showed his successful New Look, New York’s reputation, so firmly established, remained secure. Bill Blass used taffeta woven in a pale pink gingham check and tucked in at the bodice for a striped effect in this 1988 short evening dress and bolero trimmed with black lace.

New York was not just a center of high fashion, although it had numerous couturiers, including Mainbocher, Charles James, and Valentina, along with deluxe ready-to-wear designers like Norell, but of quality fashion at every level. Just as there were several different types of American women, so there was great variety in what was being designed. The most important category of fashion, and the one unique to America, was that of sportswear. Claire McCardell, Tina Lesser, Clare Potter, and Tom Brigance brought in tremendous inventiveness to their clothes, which sold for a twentieth, thirtieth, and even fortieth of couture prices.

Fashions were produced elsewhere in America, in Chicago and particularly in California, where an industry had grown up around the active sports scene and the Hollywood movies, but New York was where Americans wanted to shop. It was where the American fashion magazines were published and where the vast majority of clothes were produced. It was a magnet that drew art students from around the country to study, many to discover that their creativity would be best put to use designing clothes.

New York was the place to be. New York was where style and fashion were most closely synchronized.

New York dressed America.

Text and annotation images and image captions from the 1989 edition of Caroline Rennolds Milbank’s book New York Fashion: The Evolution of American Style. Featured visual based on a Vogue 1928 cover from the Condé Nast Store. Vogue 1938 cover image from AmericanFashionMagazines.com. Madame Demorest's Emporium image from CivilWarTalk. References does not own the legal rights of any of these images.